Copyright and Related

31 of January,2014

Acceptance of a fair use defense for appropriation artists

Por: Diego Guzmán - Investigador

Diego Guzmán

Diego Guzmán

Investigador

Keywords: fair use, appropriation artists, photographs, rasta

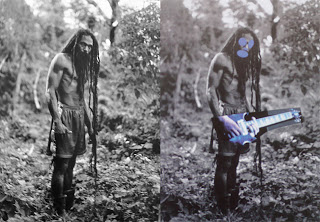

On April 2013, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit issued a controversial decision holding that Richard Prince’s use of twenty-five photographs taken from Patrick Cariou’s book “Yes Rasta” did not infringe on Cariou’s copyrights. The court held that Prince’s images “[gave] Cariou’s photographs a new expression”[1] in that they differed from Cariou’s in character and aesthetics. As a result of the court’s holding, the appropriation artists may now adopt a fair use defense as a mechanism to avoid the requirement of an authorization from other artists to create what may otherwise be considered derivative works.

Patrick Cariou, a professional photographer, published the book titled “Yes Rasta” in 2000. The book is a compilation of portraits and landscape photographs taken while Cariou lived among Rastafarians in Jamaica. Richard Prince, on the other hand, is an appropriation artist. Prince is known for the use existing objects, including works by others artists, which are then intervened to create new works. Cariou’s complaint was triggered by Prince’s unauthorized use of the photographs found in “Yes Rasta”, which were fully or partially incorporated into thirty of Prince’s artwork series. As both parties moved for summary judgment, the appeals court decided that twenty-five of the thirty disputed artworks made fair use of Cariou’s photographs. The court issued no opinion in regards to the remaining five artworks and remanded the case back to the district court to determine whether those infringed on Cariou’s copyrights.

The Second Circuit’s holding was guided by Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976, which defines what may constitute fair use of copyrightable works. The act lists various purposes for such fair use, including comments on the work itself, news, teaching, scholarship, and research. The list is not exhaustive and, therefore, other uses may be allowed. At the same time, the list does not imply that an unauthorized use of a work for the purposes listed above would be safe from an infringement action. To determine whether an unauthorized use of work can be safeguarded by a fair use defense, four factors must be considered.

First, it is mandatory to determine whether the use of the original work by the alleged infringer had a commercial purpose, transformed the work in any way, or if it was intended as a parody or a satire. It also analyzes the bad faith that could exist in the use. It held that Prince’s works significantly transformed twenty-five of Cariou’s photographs since the “composition, presentation, scale, color palette, and media are fundamentally different and new compared to the photographs, as is the expressive nature of Prince’s work.”[2] The court concluded that the commercial purpose of Prince’s work was inconsequential stating that even though “there is no question that Prince’s artworks are commercial, we do not place much significance on that fact due to the transformative nature of the work.” The court in its reasoning relied on Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 578-79 (1994) where the court held that “[t]he more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use.”

The earlier decision in Blanch v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244, 249-50 (2d Cir. 2006) shows a more thorough analysis. There, the artist Jeff Koons created the artwork “Niagara” by intervening Adrea Blanch’s photograph called “Silk Sandals” which appeared in the August 2000 issue of Allure magazine as part of an advertisement campaign for the brand Gucci. The court in Blanch v. Koons held that:

“[t]he test almost perfectly describes Koons’s adaptation of “Silk Sandals”: the use of a fashion photograph created for publication in a glossy American “lifestyles” magazine — with changes of its colors, the background against which it is portrayed, the medium, the size of the objects pictured, the objects details and, crucially, their entirely different purpose and meaning — as part of a massive painting commissioned for exhibition in a German art-gallery space. We therefore conclude that the use in question was transformative.”

The description of Koons’s artwork is relevant because of its objectiveness, since the analysis to determine how transformative the new work is, is presented from a viewpoint of a lay observer. This is precisely what Wallace, J., Senior Circuit Judge, meant in his partially dissenting opinion to the Cariou v. Koons decision when he quoted the Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co., 188 U.S. 239, 251, 23 S.Ct. 298, 47 L.Ed. 460 (1903) (Holmes, J.) stating that “it would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of [a work], outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits.”

Another difference seen in Blanch v. Koons is that the decision was also supported in dicta established in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose referring to how a satire required a lower level of transformation from the underlying work in order to comment on it. The court in Blanch v. Koons concluded that “[w]hether or not Koons could have created “Niagara” without reference to “Silk Sandals,” we have been given no reason to question his statement that the use of an existing image advanced his artistic purposes.”

The second factor of the fair use analysis deals with the nature of the original work. It considers whether the underlying work belongs to the core of copyright protection or its periphery. It also guards freedom of speech by observing if the work had already been published when it was used without authorization. Although the court acknowledged that this factor weighed against fair use, it decided this factor to be not as relevant as the others because of the high degree of transformation of Cariou’s photographs in Prince’s artworks.

The third factor considers the amount and substantiality taken from the original work. The Second Circuit saw this factor as weighing in favor of fair use by acknowledging that the factor not only refers to the quantity taken from the work, but also the quality of what was taken. It held that “Prince used key portions of certain of Cariou’s photographs. In doing that, however, we determine that in twenty-five of his artworks, Prince transformed those photographs into something new and different and, as a result, this factor weighs heavily in Prince’s favor.”

The fourth factor discusses the effect of the use of the secondary work in the market of the original work. The court decided in favor of fair use for “[t]here is nothing in the record to suggest that Cariou would ever develop or license secondary uses of his work in the vein of Prince’s artworks. Nor does anything in the record suggest that Prince’s artworks had any impact on the marketing of the photographs. (…) Prince’s work appeals to an entirely different sort of collector than Cariou’s.”

It is clear why the Cariou v. Prince decision is so controversial. By ruling in favor of Prince on twenty-five out of thirty photographs, the Second Circuit lowered the standard on the degree of transformation in secondary works. In addition, the court ignored the principle established in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose on the dangers of allowing a judge, who lacks expertise in the art field, to establish the worth of an artwork. As a consequence of this decision, the appropriation artists may now be able to easily avoid requesting authorization from other artists to create derivative artworks.